Note: This post is an updated version from my previous personal blog.

My formal mindfulness practice started in 2014 when I read Sam Harris’ book Waking Up. I had always been interested in meditation since I was a kid, but never really understood what it was or how simple it could be. Simple is not always easy. I made several attempts at various types of meditation over the years but Sam Harris’ Looking for the Self 27-minute exercise solidified my practice. From there I downloaded the Headspace app. I used it off and on for a few years. Until this past year, my meditation practice was at best, periodically consistent. At times I meditate several times a day, while other times I completely neglected it for a month. Over the past year I have strived to meditate for at least 12-minutes a day, three to five days a week. For many months I doubled this to meditating twice a day, or sitting for longer periods. This is in large part to my mentor Pete Kirchmer as part of the mPEAK certification process.

Through my meditation practice, I’ve noticed two things. One, I feel much better when I’m actively engaged in a mindfulness practice. Two, mindfulness is not a cure-all for everything. I’ve learned you can’t just meditate all your stressors away. Clinically or theoretically speaking, mindfulness concepts are only integrated into four of the six ACT principles. Part of the reason I started Flexible Responder, is to teach first responders to go beyond mindfulness practices toward true psychological flexibility which includes experiential acceptance, present moment awareness, connection with their values, and committed action toward those values.

I was exposed to a form of mindfulness well before I read Waking Up. Ellis Amdur taught my first Crisis Intervention Training course I attended. In that eight hour block, Ellis taught us several circular breathing techniques for high stress or dangerous situations inherent to law enforcement. Ellis taught that by practicing these circular breathing techniques, the habit could become second nature when needed in a time of crisis.

Since learning this technique, I’ve implemented it during code runs to shootings, active domestic violence disturbances, drownings, and officer involved shootings. In his book The Coordinator: Managing High-Risk, High-Consequence Social Interactions in an Unfamiliar Environment, Amdur explains that maintaining a tactical advantage gives you more room in which to operate. There is a dichotomy of communicating confidence between unnecessary posturing and having a presence which makes it clear to a potential offender that they will lose should they result to violence. Amdur writes:

“[We] must retain an understanding that [our] role is to exert power, however subtly, to influence a problematic social interaction to the best outcome…this active stance will give you more ‘room’ to operate – your confidence makes you the ‘eye in the hurricane’. The chaos begins to revolve around your ‘stable center. Therefore, you do not have to picture or pretend to be in control, when that is impossible (or such a display is unnecessary or tactically unsound).”

– Elis Amdur

My Own Experience

I had a similar practice while training with our Non-Compliant Visit Board Search and Seizure Team (VBSS) in the Navy. I was always able to achieve the Sharpshooter qualification with both the M9 Service Pistol and M4 Carbine, but always fell a few points short of Expert. One morning while running through our qualification course at the Kitsap Rifle & Revolver Club nestled in the woods of the Kitsap Peninsula, I took a moment to relax and breathe. It was just a few minutes of deliberate breathing and taking in the surrounding trees as I waited for the shooters ahead of me. Afterward, I was able to qualify expert on the combat course. Ever since then I’ve noticed when I take a moment to do the same, I shoot better. When I don’t, and my mind isn’t on the task at hand, or not in the zone, I don’t perform as well.

This reminded me of one of my favorite scenes, maybe the only scene I liked, from Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace. During the light saber battle against Darth Maul, Obi Wan and Qui-Gon Jinn are hindered by energy doors that close and open in short intervals which prevent them from engaging their enemy. When Qui-Gon is isolated from Darth Maul, he drops to his knees and briefly meditates in the midst of close quarters combat. Maybe this is a bad example, because ***SPOILER ALERT*** Darth Maul defeats Qui-Gon immediately after.

Pay attention to your breathing the next time you attend defensive tactics training. There is a reason your instructor constantly reminds you to breathe. In a force encounter we tend to stop breathing under stress. I see this happen in training. When we stop breathing we don’t move as efficiently. Our brains don’t perform optimally when aren’t circulating oxygen. When we forget to breathe, we tense up and tire out quickly. Bike trained officers are taught this. When sprinting to a critical incident like a help-the-officer, or even during a foot pursuit, it’s important to keep breathing. Don’t over exert yourself. There will likely be a fight once the chase ends or you arrive. You’d better have enough fight left in you. It could be a fight for your life.

I was reminded of that in my second Jiu Jitsu competition. I went all out for five minutes in my first match. Even after a five minute break, I was completely gassed and had nothing left for next match. I was quickly dominated and submitted. Breathing alone won’t fix or prevent this from happening. An awareness of your breath and body movement coupled with high intensity interval training will greatly improve your capacity and stamina.

The Methods

Belly Breathing

Belly breathing is a technique often done laying down, but it can be done standing up, sitting down, or even throughout many movements. The belly breath, or three part breath is the foundational breath of yoga. At first it may be useful to place your hand on your stomach as you practice this mindful breath work. As you inhale, allow your stomach to rise. Let it fall on the exhale. The three part breath starts with the rising of the belly, then to expansion of ribs, and finally filling and expanding the chest. As you breath in, it helps to say to yourself, “belly, ribs, chest” on the inhale, and “chest, ribs, belly” on the way out. The practice of the three part breath may strain the inner costal muscles between the ribs at first. This is because we’re not used to breathing in this manner. It doesn’t take long to acclimate. Belly breathing is foundational for the following breath work techniques.

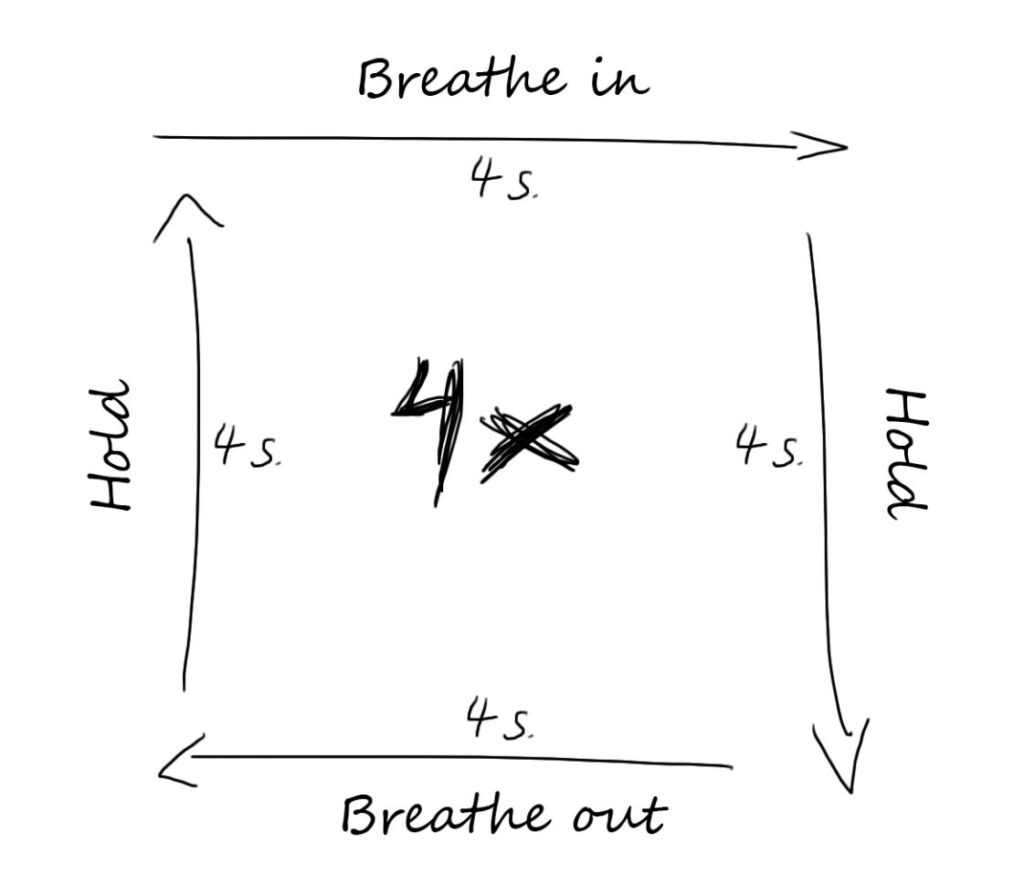

Tactical or Box Breathing

I imagine calling this method tactical makes it more accessible for anyone who’s ego may prevent them from trying a mindful breathing exercise. This is also called box breathing. You can utilize this anytime you’re feeling overwhelmed or under stress. It doesn’t have to be used while facing danger on the street, it’s just as useful when presented with the frustration of an incompetent leader or facing micromanaging boss.

- Simply inhale, briefly hold the breath then exhale.

- You can breath solely through the nose, or in through the nose and out through the mouth.

- Start by counting the the duration of the breath: In for a count of four. Hold for four. Out for a count of four.

- Use any pace you can comfortably manage. The count isn’t fixed either. You’re out breath could be more extended than your inhalation. You could pause at the top of your breath for a shorter amount of time.

- Try starting with the four count series four times. Play around with it. Notice how you feel before and after you’re done.

You can do this breathing excursive wherever you are. It doesn’t matter if you are sitting or standing. Like I said earlier, I’ve done it while driving. I’ve even implemented it during Jiu Jitsu competitions just prior to stepping onto the mat to face my opponent.

- Breathe in through your nose.

- Visualize the air moving down in a line toward your naval as you breathe in. Fill your belly with air.

- Pause at the end of your inhalation.

- As you exhale through your nose, visualize the air moving from your belly, up the back of your spine, over the back of your neck and head, in a complete loop, then exiting out your nose.

There are a few different ways to do this breathing exercise. Rather than visualizing the air moving down through the body and up over the head, some people prefer to reverse it, and visualize the air moving in over the head, down the back, up the belly and chest then out the nose. You can take this method a step further and visualize the air as blue, cool, and calming when you inhale. As you exhale visualize the air as red, hot, and tense. This way you visualize replacing the tense stale hot air with fresh cooling and calming air.

Recovery Breathing

I learned the recovery breath from the YFFR Instructor course. The recovery breath is simply the three part breath with a longer exhalation. Ideally, the recovery breath is done by inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth. It can be as short as a count of in-for-three and out-for-five. The recovery breath has an immediate effect on down regulating the body’s fight or flight system. It can help to purse the lips on the exhalation, as if breathing out through a straw. The count doesn’t necessarily matter, it’s the extended exhalation which causes the down regulation. There are two reasons the recovery breath works. First it is believed to stimulate the vagus nerve, which down-regulates your body’s fight or flight response. Second, when we exhale the diaphragm moves in such a way that it makes more room for the heart. This space allows the heart rate to slow down and pump more blood, which contributes to the down-regulation. Try the recovery breath the next time you feel activated, after the event is over, when you notice you feel heightened, or up-regulated, either physically or mentally notice the sensations in your body like your heart and respiration rate. Try the recovery breath and check in with your body to notice any changes.

Physiological Sigh

What I love about the physiological sigh, is that it has an immediate effect on the nervous system. The physiological sigh is having a moment right now, thanks in part to Wim Hof and Dr. Andrew Huberman. The physiological sigh is a pattern of breathing which we naturally engage in during deep sleep, or even while crying. This breathing pattern is a double-inhale with an extended exhale. The physiological sigh helps off-gas carbon dioxide. Research shows 1-3 breaths of the physiological sigh has immediate impacts on improving our stress response. Dr. Huberman further recommends a protocol of setting a timer daily for 3-5 minutes to practice the physiological sigh.